Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

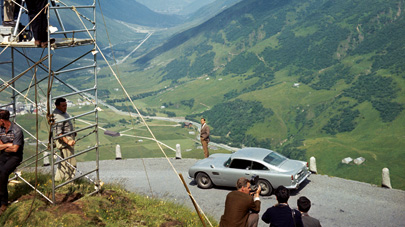

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE

CENTENARY

DRIVEN TO SUCCEED

David Brown, whose “DB” moniker still adorns Aston Martin’s flagship Grand Tourer today, was a charismatic individual with a love of machines and a hunger for life, writes David Burgess-Wise

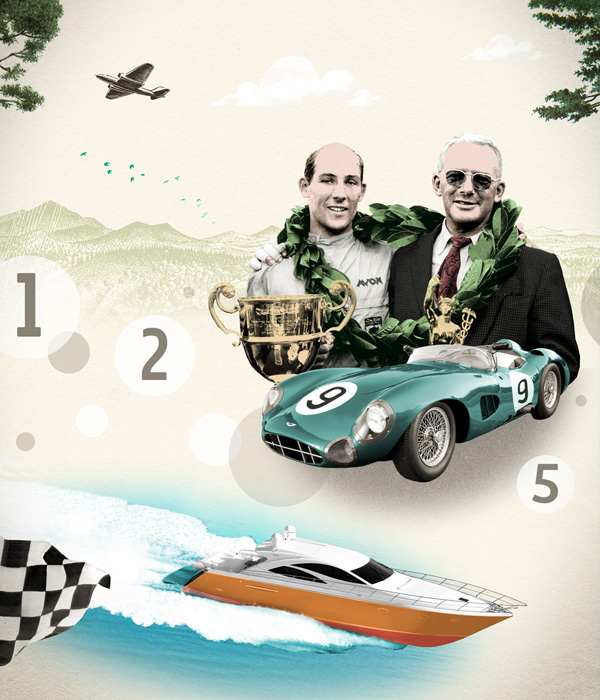

Illustrations: Valero Doval

“DB”, PERHAPS THE BEST-KNOWN INITIALS IN THE MOTORING WORLD, are those of Sir David Brown, the Northern industrialist who, back in 1947, bought the moribund Aston Martin company out of his own, admittedly deep, pockets for £20,500. Then, like some modern alchemist, he married the fine-handling but underpowered Aston chassis with the remarkable twin-cam six engine of the Bentley-developed Lagonda (another of his personal purchases) to create the handsome Aston Martin DB2, the first in a line of “DB”-badged sporting legends. He also initiated a racing programme that brought worldwide fame to Aston Martin, culminating in 1959 with victory in the World Sports Car Championship, the first time this ultimate prize had been won by a British team.

David Brown’s need for speed had been nurtured early. As a child scarcely out of the perambulator, he had ridden on a soapbox seat alongside engineer Frederick Tasker Burgess during test runs on the bare chassis of the “Valveless” two-stroke cars for which the gear-manufacturing firm, founded by David’s grandfather in Huddersfield in 1860, had acquired the production rights in 1908. The lad sometimes accompanied Burgess, who in 1919 became a member of the team that designed the 3-litre Bentley, on delivery runs to the coachbuilders in London. Later, when David was 11 or so, Burgess taught him to drive, with wooden blocks to extend the pedals and extra cushions behind his back.

David Brown’s mother helped, too. A keen motorist, she had been the first lady driver in Huddersfield and probably the second in Yorkshire. “My father, on the other hand,” recalled Sir David many years later, “never learned to drive and knew nothing about cars.”

Brown was literally born into the company in 1904—his birthplace, Park Cottage, stood within the 17-acre site of the family firm’s Park Works in Huddersfield—and was steeped in the family business from a very early age. Every Sunday, his father Frank took him to the factory and explained the contents of each letter in the company mailbox, a practice carried on during the unfortunate youth’s school holidays.

Brown recalled that he passed the usual examinations, did not particularly distinguish himself, and went straight into the family business in 1921 as an engineering apprentice. Given a thorough grounding in all aspects of the company, young Brown enjoyed no favours. Even though the family home was over six miles from the factory, he had to clock in promptly at 7.30am each day. His father offered to buy him a motorcycle to help him get there on time: young David played a cunning hand, no doubt banking on his father’s ignorance of things motoring, and bought a 1100cc Reading- Standard rather than some docile runabout. Built in Reading, Pennsylvania, the Reading-Standard was a V-twin with strong competition credentials, and Brown lost little time in entering local hillclimb competitions. He recalled: “I hotted-up the Reading by raising the compression ratio, drilling the con-rods, lightening the fly-wheel and fitting narrower mudguards.” His performance in those local events—he made the fastest time of the day on the notorious Axe Edge Moor in Derbyshire—brought him to the notice of the Douglas motorcycle company, who invited him to be reserve rider in their Tourist Trophy team. “I went to the Isle of Man for practice,” he remembered wryly, “but my father got to hear of it and that was that!”

By now, Brown was romantically involved with a young woman named Daisy Muriel Firth, three years his senior, who he had known since he was 14. In an attempt to cool his ardour, Frank Brown sent his son to South Africa in 1922 to help a company director oversee the installation of David Brown gears in gold mines near Johannesburg. However, off the corporate leash, the director was drunk most of the time and the youngster had to take responsibility for the installation. “I grew up very fast in South Africa!” Sir David remarked.

“Young David played a cunning hand, banking on his father’s ignorance, and bought a 1100cc Reading-Standard rather than some docile runabout”

On his return, the precocious youngster, who had already written a practical handbook on gear making, decided to build his own car, working at a drawing board in his bedroom each night until 2am, designing a 1.5-litre twin-cam, straight-eight engine (an advanced type of power unit then found only on Grand Prix racers). Using the firm’s foundry, he made patterns and cast the cylinder block, then produced components in the machine shop. When his autocratic father caught his son working on the project in company time, he furiously put a stop to it. Undaunted, young David made a chassis frame, and installed a proprietary 2-litre Sage engine and Meadows gear box. He called his home-made car the “Davbro”, and continued his courtship of Daisy in it. They were married in 1926, much against the wishes of David Brown’s parents, who refused to attend the wedding.

Nevertheless, that year Brown completed his apprenticeship and became foreman in the worm-gear department; prophetically, he was soon producing final drive gears for a new Aston-Martin designed by “Bert” Bertelli that made its debut at the 1927 London Motor Show at Olympia.

Another early commission, thanks to the unique gear-grinding skills of the David Brown Company, was building a supercharger for the Vauxhall racer belonging to Raymond Mays. Young Brown was given the job of liaising with the supercharger’s designer, Amherst Villiers. Knowing that Villiers had enough spares to build a second Vauxhall racer, Brown agreed to build the supercharger on condition that Villiers sold him those spares for £100.

When it came to testing the newly installed supercharger in Mays’ Vauxhall, Brown suggested using Holme Moss hill in the Pennines near the factory, where he used to practise with his motorcycle. The tests had to take place in the early morning to avoid traffic, but Raymond Mays was late.

Impatiently, Villiers asked David Brown to drive the car. “I think he was surprised at the manner in which I conducted it up and down the hill, which I knew backwards!” recalled Brown. “The next morning, Ray came out for the tests and he couldn’t go as fast as I had, because I knew the hill so well.”

The delighted Villiers agreed to sell his spares to Brown to build a second Vauxhall racer, provided that the car was fitted with a Villiers supercharger (no problem, since this would be built by the David Brown Company) and had “Amherst-Villiers Superchargers” painted in six-inch letters on the bonnet.

Brown cut the chassis down by about six inches and made it underslung, fitted a worm-drive axle of his company’s own make with a lockable differential, “and it won its class every year for about three years at (hill-climb track) Shelsley Walsh”. It was also successful in sand racing at Southport, where it won at least 13 races; its top speed was said to be 140mph!

David Brown oversaw Aston Martin’s return to sports car racing, achieving success with such cars as the DBR1 and Stirling Moss behind the wheel, and leading to famous victories at the Nürburgring and Le Mans in the 1950s

He didn’t attend another motor-race meeting until after the war. There was still, however, a motor sport connection, with the David Brown Company supplying gears for Sir Malcolm Campbell’s Blue Bird land-speed record car and making Roots-type superchargers for thoroughbred sports cars, including the near-legendary Squire, of which only seven examples were built between 1934-36. David Brown had already introduced new and more efficient working practices when charged with turning round a loss-making subsidiary in Keighley in the late 1920s. Under his leadership, the parent company expanded significantly, opening a new foundry at Penistone in 1935.

In 1936, Brown, who had bought a farm, started building Ferguson tractors in a corner of his gear factory; the Ferguson-Brown was the world’s first production tractor with hydraulic lift and converging three-point linkage, a design concept quickly adopted by other manufacturers worldwide. Inevitably, there was soon a falling out over design between Brown and the equally strong-willed Irishman Harry Ferguson, which led to the introduction in 1939 of the David Brown tractor, built in a former silk mill at Meltham under chief engineer Georges Roesch, former designer of the London-built Talbot sports cars that had done so well at Brooklands and Le Mans. Orders for 3,000 were taken when it was launched at the Royal Show in Windsor.

“David Brown had a simple management philosophy: ‘Get a good man and let him get on with it. If he is no good, get another man. But if he is good, support him.’ ”

World War Two saw further expansion, with the Park Works making gears for all types of machines and vehicles, including the Rolls-Royce Merlin aeroengine. In 1940, the aero-gear division moved to Meltham, supplying gears for Bristol Hercules radial aeroengines and Spitfires. A tank gearbox division also opened at Meltham, which also made airfield tractors for towing aircraft and bomb trolleys, while Penistone produced armour plating for Churchill and Cromwell tanks and steel casings for blockbuster bombs. A foundry was built at Penistone that made castings for aeroengines and cables for “PLUTO”, the “pipeline under the ocean” that supplied fuel for the D-Day Normandy landings.

David Brown had a simple management philosophy: “Get a good man and let him get on with it. If he is no good, get another man. But if he is good, support him.”

This left him time for his diversions, far wider than Aston Martin Lagonda. He bred hunters and racehorses on his 700-acre farm in Buckinghamshire, his biggest success being victory in the 1957 Cheltenham Gold Cup with Linwell at odds of 100-9. During the winter he spent most weekends hunting; he was joint Master of the South Oxford hounds. In the summer he played polo at Ham Club, where they still compete for the Sir David Brown Trophy, and with the Household Brigade at Windsor.

He spent his more leisurely weekends in the 1960s aboard his 200-ton diesel motor yacht, Astromar, based at Poole Harbour. His nautical interests were reflected in his group’s acquisition of a controlling interest in high-speed launch manufacturers Vosper in 1964. In later years, he moved to Monte Carlo as a tax exile, always with a luxury yacht in the harbour. His last yacht was the catamaran Chief Flying Sun, built in South Africa in the early 1990s; its name reflected his induction in 1959 as Chief Flying Sun of the Iroquois Tribe of the Mohawk Nation.

A keen pilot as well as an expert driver, David Brown established his own airfield at Crosland Moor, a couple of miles south-west of Huddersfield. He had his personal De Havilland Dove, normally flown by his personal pilot Phil Anscombe, upholstered with leather in the Aston Martin trim shop.

His keen interest in the racing side of Aston Martin saw him employ John Wyer, the best team manager in Britain, who, in David Brown’s quest for victory at Le Mans, hired some of Britain’s finest drivers of the 1950s, such as Stirling Moss, Tony Brooks, Peter Collins, Roy Salvadori and Reg Parnell.

Nor was he a remote team owner, as Roy Salvadori, a personal friend, remembered: “My main impression was his closeness with the team. It is not every patron who would stay in the same hotel and mix with the team members, as he did at Le Mans and elsewhere. He knew all the mechanics by name and he made friends with his drivers. He didn’t have to and most top men don’t, they keep their distance, but we were friends rather than employees. He continued to keep in touch with us to the end.”

In 1972, financial considerations saw Sir David —he was knighted in 1968—sell both Aston Martin Lagonda and his tractor division, which had become Britain’s third largest farm tractor manufacturer and held the Royal Warrant. It seemed like the end of the “DB” legend.

However, some 20 years later, Walter Hayes, the then Chairman of Aston Martin, sought the octogenarian Sir David’s permission to revive the signature “DB” initials for the new “NPX” model being developed under Ford ownership. It was a permission that was delightedly given, and “NPX” duly became the DB7.

In 1993, Sir David Brown died in Monaco, his need for speed still unslaked, as Walter Hayes recalled to me at the time: “David Brown was a vigorous and wiry old speedster until his last days. At 89, he complained that his catamaran wouldn’t do more than 34 knots, took the engines out and sent them back to Germany!”

CENTENARY

Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE