Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE

THE DRIVE

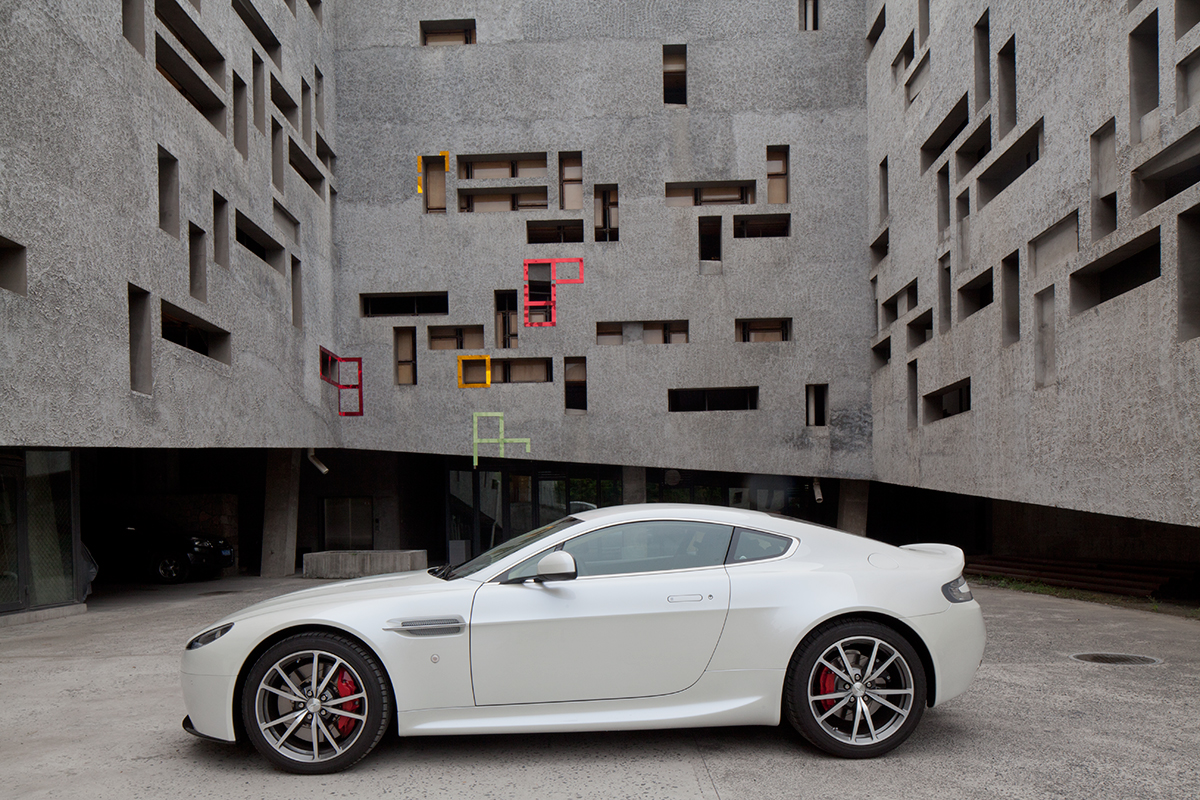

The V8 Vantage outside the China Art Academy’s Foundation and Experimental Department

NEW HORIZONS

Christopher St Cavish TOURS SHANGHAI AND BEYOND IN a V8 Vantage to discover the work of Wang Shu, THE ARCHITECT TRANSFORMING CHINESE URBAN DESIGN

Photographs: Daniel Traub

Fascinating forms at the China Art Academy’s Architecture School in Hangzhou.

“Where is China?” Wang Shu’s feet were on its soil but the answer eluded him. It was 2000 and he was an anonymous student, nearing graduation with a PhD from Shanghai’s prestigious Tongji University. The administrators came to him, embarrassed that he had slipped through their architecture programme unknown. This was many years before he’d win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s closest award to a Nobel, rocketing his name around the globe. He was a modest, eclectic architect with a few small projects under his belt, not yet a young master blazing a new trail, not yet the architect Harvard professors would praise for finding a “radical means to achieve traditional forms”. He was a painter at heart, a scholar second, and a craftsman third, who found a framework for all of these interests in architecture.

“Join us. We’ll make an exception for you. Be a professor.” The school offered to bend the rules. They wanted him to stay in Shanghai, a city that was beginning to boom again after decades of dormancy. It needed teachers. Wang Shu looked around. “Shanghai isn’t China,” he told the school. “Hangzhou is China. I want to work in China.” And with that, he was off on a path to become one of a handful of Chinese architects conceiving a new, truly Chinese, architecture style. Creeping down Century Avenue in a V8 Vantage, a six-lane highway that passes for just another oversized street in Shanghai’s oversized Pudong District, Wang Shu’s words could not be more apt. The district was a few warehouses, docks, farmers and farmland only three decades ago. Today, it has five million residents and a forest of skyscrapers. It is Shanghai’s future, part of the city’s ambition to be a world capital, realised in steel and glass and infrastructure.

The V8 Vantage purrs its way down the broad avenue, as mirrored facades of international banks and five-star hotels pass by the window. On the driver’s side, the 88-storey Jin Mao Tower looms, a nouveau skyscraper, which is meant to evoke a tiered pagoda. Behind, the 101-storey Shanghai World Financial Center, finished in 2008, cuts upward like a glass and steel knife-edge. For now, these two buildings dominate Shanghai. But change is in this city’s DNA. The half-dressed Shanghai Tower stands just beyond, the last steel beam recently put into place 632 metres above ground. It will be the world’s second-tallest skyscraper when it is completed in 2015, an all-too-literal metaphor for the incredible gains this city of 23 million people has made in a whirlwind decade.

We coast into the tunnel under the Huangpu River and emerge into old Shanghai—the past. Grand 19th-century buildings flash by on our right, placeholders of the city’s European history. I tap a finger on the paddle of the seven-speed Sportshift II™ transmission, and the 4.7-litre, 430 bhp V8 engine zooms us up onto the elevated highway, headed to Hangzhou. Headed to China. Negotiating busy Chinese cities as a motorist is never dull, but driving on the highways is pure pleasure. The country’s infrastructure boom has spawned dozens of airports, new Metros for countless cities—and smooth, wide expressways with more space than cars. An hour outside downtown Shanghai on the highway, a biblical rainstorm erupts. We ride it out, the low centre of gravity of the V8 Vantage’s engine making the car sublimely easy to handle, even in the downpour. The rain rinses off the pressure of the big city, and the lush green mountains that border Hangzhou start to appear.

“Hangzhou is a landscape,” Wang Shu says. “The entire city is landscape. You can’t separate its architecture from nature.” A thousand years ago, Hangzhou was the capital of China, a highly refined city of a million people with a reputation for literature and the arts that remains to this day. There are still willows and stone bridges around the edge of West Lake, the heart of the city. Pagodas rise up between the lake and the tea fields beyond. “Landscape is a religion for the Chinese,” says Wang. “For 1,000 years, Hangzhou was half landscape, half city. Twenty-five years ago, it was like a nuclear bomb went off.” The urban area didn’t sprawl, it exploded, growing 10 times its size in two decades. China’s architects at the time were not interested in addressing the imbalance, according to Wang. “Chinese people wanted to be new, to be powerful so they destroyed the traditional buildings. They wanted to be America. They didn’t want to be China. I had to react. China needed another kind of architect.”

A fork of lightning descends upon Hangzhou, as seen from the passenger seat of the V8 Vantage.

For much of the past decade, Wang has formulated this counter-strategy at a rural campus of the China Art Academy, developing a new form of modern Chinese architecture, “based on Chinese culture, from the earth, from the land, from local traditions, not an abstract concept.” He is dean of the School of Architecture but his influence is pervasive—he designed all 23 buildings on the 13sq km site.

The campus is a repository of Wang’s ideas and a place for him to express his philosophical approach, which incorporates everything from Buddhism and Daoism to first-hand knowledge of carpentry and bricklaying, gleaned from years of construction work. He sees the Buddhist temple as the blueprint for this Xiangshan campus, with glassed enclosures on the roof of some buildings reflecting the traditional reading rooms for scholars, purposefully empty spaces which act as meditative caves.

Crossing the Hangzhou Bay Bridge, the world’s longest ocean bridge

The courtyard of a home, says Wang, is where families find paradise, where nature and family meet. All of Wang’s buildings feature such a paradise, with courtyards of varying sizes and abstraction. Some are planted with delicate bamboo or feature red-brick floors overlooked by burnished, hinged bamboo doors. Thick ivy climbs up grey brick walls, bright orange honeysuckle tumbles over connecting walkways and pools full of lotus flowers bloom in brilliant pink and white. In his most literal connection to nature, one overgrown walkway leads directly from a building to a large hill, dead-ending into a wall of orange earth. And standing out on the campus is the Entrepreneurship Building, a singular and discordant structure with a much less natural feel—a striking stack of large concrete slabs and slick, modern glass.Wang developed this campus as a painting, not a blueprint. He explains the relationship between the building and the hill that anchors the campus, through the perspective and scale of ancient Chinese landscape paintings. Wang is fascinated by the idea of seeing multiple sides of the same object at once, something both Chinese landscape painters and the Cubists have experimented with. He took inspiration for two stunning grey brick buildings with sloping roofs from ancient scrolls showing the ripples of a lake, which he refers to as being a “wave of water”.

He laments the absence of this philosophical underpinning in Chinese architecture, though has pointed out that only a century ago, there were no Chinese architects. Craftsmen ruled the day. To this day, as he decries the changes that China’s boom has had on society, he takes faith in China’s craftsmen. His heritage plays a part. His father was a keen carpenter, and talking about him, he could be commenting on Aston Martin’s heritage: “I was amazed at how great things could be created by deft hands.” The combination of philosophy, respect for tradition and a grounding in hands-on skill is the legacy he is looking for. “I want my students to become philosophical craftsmen, equipped with both thinking and technique.”

We stop in front of the recently completed Wa Shan complex, an angular, connected set of five buildings. Dramatic lighting highlights the raw-wood frame of the roof and the burnt orange of the rammed-earth walls, a local building technique. The sharp lines of the structures and a ragged opening in the wall, contrast with the long, low bonnet line and broad rear haunch of the V8 Vantage. The car’s understated confidence draws in families out for a stroll and design students spending the summer on campus, each eager to peek into the two-seat, leather cockpit. The V8 Vantage feels like it belongs here—a lesson in proportion and sculptural form in itself. For Wang, the Xiangshan project is also about city living and memories. “The campus is about finding a high-density model that still allows you to live and move within a landscape.” The beds of bright yellow sunflowers are a reference to the 1950s and 1960s generation raised amidst the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution. “School was stopped and the teachers were ordered to raise crops on university grounds.”

On our way back through Hangzhou, we follow the Qianjiang River, once on its eastern edge but now in just one of several business districts. This is the site of Wang’s only commercial residential project, the Vertical Courtyard Apartments, an experiment in scale that is meant to restore some of the anonymity of high-rise towers. As we slow down to cross the bridge over the wide river, the building’s stacked appearance, evoking a tower of two-floor houses laid one top of the other, each slightly askew, immediately stands out. We park on a back street. The V8 Vantage’s swan-wing doors swoop upwards in a graceful arc, catching the light, as grandparents point the car out to their grandkids. We head to the roof of one of the towers, where we find a 26th-floor community garden, struggling in the summer heat. Down below, a barge chugs along the coffee-coloured river and the V8 Vantage’s white roof glistens up at us. From the Vertical Courtyard Apartments, it’s a two-hour drive to Ningbo, a one-time treaty port on the East China Sea. Ningbo was the original Shanghai, a magnet for rich Chinese from the south and traders from Europe, until taxes and strife drove its wealthiest and smartest financiers up to Shanghai proper, where they laid the foundation of the city’s notorious financial savvy. These days Ningbo is undergoing what many would call a renaissance, at least in economic terms, though not Wang, who has likened China’s thirst for modernity as “destroying ourselves, destroying our roots and destroying our teachers.”

The leafy Architecture School at China Art Academy.

Wang arrived in the city in 2004, amid the destruction of many of Ningbo’s traditional villages, to take on the city’s plan for a new history museum. At the time, the site was at the edge of town, in what looked like countryside but would become yet another business district, known as Little Manhattan. The last house from the area’s former village was cleared away on the same day that construction started on the museum. He was given a blank slate. “It was like being God,” he recalls. “Before, there was nothing. You have to create from scratch. I had to find some essential reason to build something here.” He shows a landscape painting from the Southern Song Dynasty (960-1279) by Li Tang, called Wind in Pines Among a Myriad of Valleys. A rugged mountain and rock face anchors the painting as a winding rocky path cuts through a gnarled pine forest. The Ningbo History Museum became the mountain, anchoring this space between downtown and country, past and future. He started from there, creating inner and outer “valleys” among a series of asymmetrical, powerful structures. The interior is broken into intimate “caves” for scholars. Everyone enters the building through a dark entrance that appears to slide underneath and into the museum—a cave in itself.

For the exterior, Wang used a technique named wa pan, which uses a random jumble of leftover building materials—stone, brick, roofing shingles, slate—that we would later see in Cicheng, an ancient village a short drive north. But whereas in Cicheng and similar towns, the locals ignore these crumbling, dilapidated structures to show you a Confucius Temple or the estate of a one-time official, Wang saw this as a promising future, not an outdated past. This same attitude led him to collect a million used grey bricks and tiles, the building materials of the former village and ones like it, which he juxtaposed against cast-concrete, textured with a bamboo frame he has devised himself. The effect is powerful, angular and random on first glance; critics have called the space a fortress. Though construction is complete, Wang says the building is not finished. “We treat the building as if it was a plant. It is not in its best state when just completed. After 10 years, when the wa pan walls are covered with lichen and shrubs, then it will truly blend into the history of China.”

The Vantage created an appreciative stir on its journey.

We drive back to Shanghai across the 36km Hangzhou Bay Bridge, the longest ocean bridge in the world. It is a series of straightaways, well-known by owners of fast cars. In the daytime, it’s the V8 Vantage’s lean agility and handling that count, as other drivers swerve and bob, distracted by the incredible scale of the bridge. The bridge eventually becomes just another highway and I can finally open up the bypass valves and accelerate down an empty stretch of the G15 highway. The engine lets out a glorious roar and the deep bumper and carbon-fibre splitter make the car feel more stable the higher the speedometer climbs. And it climbs quickly. Outside, the industrial sprawl turns into a blur, perhaps appropriate for a country experiencing rapid urbanisation with 70% of the population expected to be living in cities by 2035. Wang has found the China he wants in Hangzhou and Ningbo, and he is leading a new generation of architects down an exciting, reflective path. “We need life, not just huge, shiny buildings. Compared to traditional Chinese craftsmanship, modern architecture is so simple. Being modern doesn’t mean we should abandon the past. We have to co-exist.”

Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE