Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE

SURFING

Mark Richards was nicknamed the “Wounded Seagull” due to his unique surfing style. He was, however, a very, very good surfer

riding

the crest of

a wave

Photo-journalist John Witzig was at the heart of the surfing revolution, which swept through Australia during the 1960s and 1970s. he reveals how he chronicled those heady days in pictures...

BEFORE A US LIFEGUARD team arrived with what were “modern” surfboards in 1956, Australians used to ride waves on 16-foot hollow plywood paddle-boards that were used for racing. They were unwieldy things, and they were dangerous. The new, lighter, smaller balsa boards had a fin, they were manoeuvrable and they were way more fun. We called them “Malibu” boards, since the lifeguards had come from California. Balsa was almost impossible to find in Australia, so we made hollow plywood versions of them. My first board was ply, secondhand, homemade and heavy. But it was 1959, and I was 15 and easily excited. I grew up in Sydney, and the surfing world in the late 1950s and early 1960s was tiny. Australia was becoming more prosperous, so more kids were getting cars. Mostly they were old cars, and often they were shared, and we began to travel around Sydney’s beaches to find good surf. Then we began seriously exploring the coastline.

Surfers were not well regarded by authority and some of that reputation was richly deserved. Before the relative freedom of the smaller boards and increasing mobility, surfers had been mostly tied to surfing at life-saving clubs on individual beaches. Boards were left at the club houses, and rudimentary accommodation was often available. Freed from the authoritarian clubs, surfers were often seen as gangs of marauding delinquents. There were splendid examples of outrageous behaviour, and despite (or because of) that, collectively, we redefined surf culture in Australia.

Bob McTavish watches the breaks at National Park in Noosa, Queensland, then a hidden gem, in the mid-1960s

Two surfing magazines were launched in 1962—Surfabout, which was based in Sydney’s southern beaches, and Surfing World in the north. So small was our sub-sub-cultural world that we, sort-of, knew everyone, not the case even a few years later. I met the early surf photographers and also Bob Evans who edited Surfing World. In 1963, Bob ran a story of mine about a surfing trip to Byron Bay, which was some 10 or more hours’ drive north of where I lived, on a highway that definitely didn’t deserve the title. I came to photography through surfing, not the other way around. I was picture-obsessed and taking surfing photographs was pretty easy. Surfing knowledge was a prerequisite, and a 35mm SLR camera and a 400mm telephoto lens weren’t that expensive. I mostly shot black-and-white film, and from fairly early on, did the processing and printing myself.

Because it was such a small world, I got to know most of the best Australian surfers in the early 1960s. We’d started to travel further afield in the search for waves, on trips that were both terrific adventures and good subjects to record. Competitions increased in importance and were great gatherings of the surfing community. The influence of California on Australian surfing was overwhelming in the early years, but by around 1965, there was a realisation that things were happening in our own backyard that were original and of real value. We didn’t appreciate it immediately, but it was the beginning of what would become the shortboard revolution, and Australian surfing would sweep away everything before it for many years.

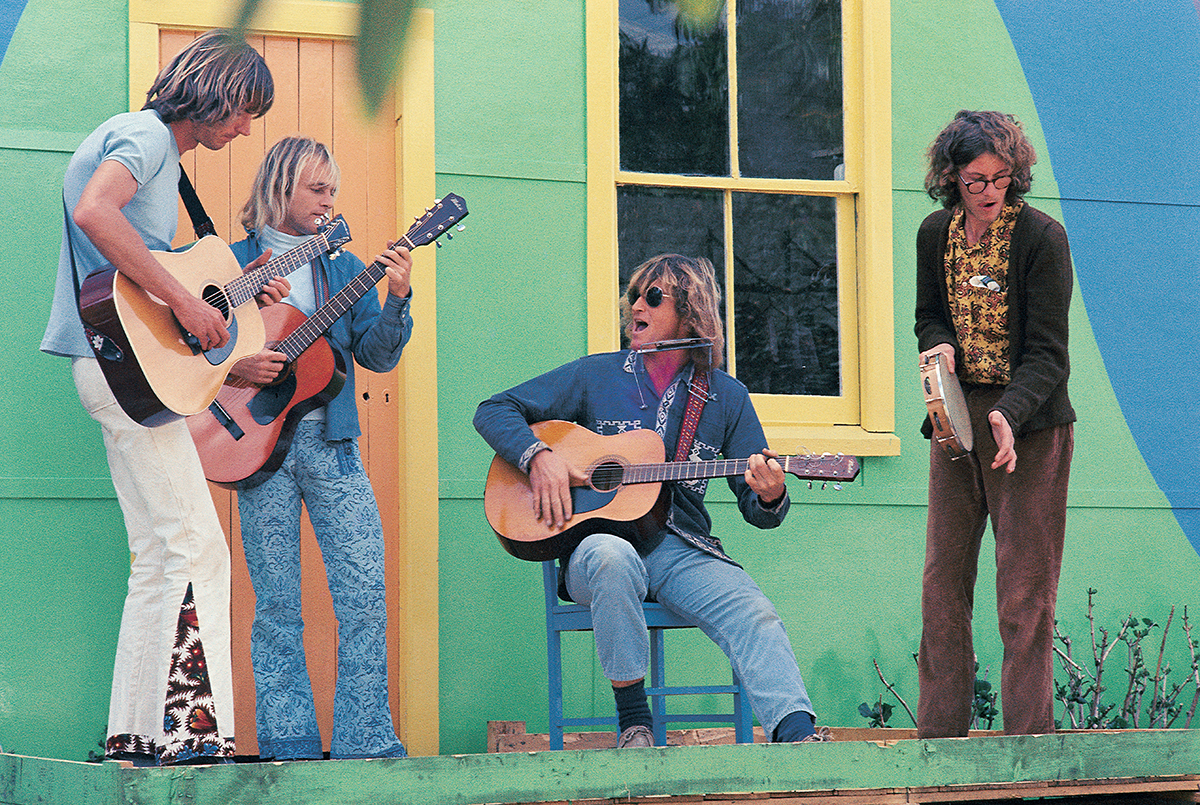

The surf community brought colour and vibrancy to towns like Byron Bay. Musicians (from left) Garth Murphy, John Adrian, Rusty Miller and Jimmy Sunshine entertain locals in late 1972 or early ’73

By good fortune, friends of mine were at the forefront of this period of great change in surfboards and performance. When Nat Young won the World Championships in California in 1966, I’d tagged along. In December 1967, I was the only stills photographer at Honolua Bay on Maui when Nat, Bob McTavish and George Greenough broke new ground in performance surfing. George was an expatriate American who was enormously influential in the development of boards that the Australians were riding. He’d been ignored in the US, but was met with a ready welcome among the rag-tag Australian surfers. These guys were the friends I surfed with. We went on a number of trips around the Australian coastline. From 1966 I was working for surfing magazines, so I had ample excuses to jump in my beloved Kombi, and drive overnight to catch a swell, hitting a favourite break somewhere up the coast. I was documenting my own life as much as that of my friends.

Fans watch the competition at Bells Beach, 100km south of Melbourne— a natural amphitheatre, which added to the attraction.

I had remarkable and privileged access to some of the most influential surfers in Australia throughout this period. Sometimes they weren’t wholly aware of the importance of what they were doing, but at other times it seemed quite clear (to some of us). Its expression, in print anyway, was wildly erratic and is sometimes embarrassing to revisit.

John’s brother Paul with his son at Cactus in South Australia, a surfers’ town where he built a house entirely made from materials scavenged from the bush

In 1966 I edited my first magazine. I had all the maturity of a 22-year-old. Of course I behaved like one, what else could I do? What’s kind of nice now is to see the moments of clarity and prescience amongst the hyperbole. There were also some spectacular attempts to describe the surfing experience in prose. They were spectacularly bad on the whole, but occasionally quite good. This was the 1960s, a period of excess and eccentricity, of individuality and also authenticity. Surfing didn’t have to try hard to meet the criteria. That it was “real” was at the heart of its adoption, maybe appropriation, from those days on, by people from way beyond its borders as a symbol of “freedom” and beauty—and also of cool. But when Middle America started wearing surf gear you had to wonder.

We can never go back to those first days of exploration and adventure, but the spirit of them survives in one boy or one girl, on one wave, somewhere

in the world, and that’s a magical thing.

A Golden Age: Surfing’s Revolutionary 1960s and ’70s by John Witzig is published by Rizzoli, New York. www.rizzoliusa.com

A house scruffy enough to be rented to a group of surfers in Torquay, New South Wales, in 1970.

Left: Wayne Lynch made occasional forays into competition in the late 1970s. Right: Bob McTavish and Russell Hughes at Main Beach, Noosa

Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE