Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE

CENTENARY

THRILL OF THE CHASE

Just as James Bond is forever associated with Aston Martin, cars have been an integral part of cinema since its earliest days, as David Gritten reveals

MANY OF US HAVE FELT THE EXHILARATION OF BEING BEHIND THE WHEEL , perhaps feeling a heightened sense of alertness as we negotiate the twists and turns of a leafy back road in rural England, or cruise along a seemingly endless American highway, surveying the breathtaking wide-screen landscape ahead. Under such circumstances, it’s not hard to imagine yourself as the star of your very own movie. Conversely, when we watch an actor in a film, driving at speed with enormous skill or under great pressure, part of us longs to swap places with them. Think Ryan Gosling as the stunt driver/getaway man in Drive, burning rubber in his 73 Chevrolet Chevelle, or the peerlessly cool Steve McQueen testing his 68 Ford Mustang GT to the limit in the classic 10-minute car chase from Bullitt.

From film’s very beginnings, audiences have responded viscerally to the spectacle of a vehicle hurtling towards and past the camera, on the way to unseen roadblocks, dangers or disasters ahead. Still photography was the immediate predecessor of film, and this kind of thrill was something photography simply could not provide. No wonder they called them the movies.

The histories of motion pictures and automobiles have unfolded along parallel lines. Both were first envisioned and introduced tentatively in the late 19th century; thanks to breathtaking innovations and sheer technical brilliance, both have developed over more than a century to a point that makes them unrecognisable from their early prototypes. Today they are widely regarded as two of the more agreeable aspects of modern living. But from the outset, it has been clear: cars and films suit each other exceedingly well.

Mack Sennett was one of the earliest film producers to grasp this fact, and his silent comedies in the hugely popular Keystone Kops series (1912-1917) gave people what they wanted. Essentially, they were about the adventures of an incompetent, clownish police force; Sennett included cars, whenever possible, for frantic chases, and as “paddy wagons”. The classic (and recurring) comic gag in the series involves the Kops dashing from the station and throwing themselves into the paddy wagon as it speeds off to a crime scene; but it speeds away so fast that at least one Kop launches himself into the air but narrowly misses it.

Cars became part of the “furniture” of movies, especially American films, after Henry Ford put the Model T into mass production in 1908. But in film’s early days they were little more than plot devices—simply a means of getting characters from one part of the frame to another. The cameras did not linger over the contours of cars. Audiences were not encouraged to care what cars were used in Keystone Kops movies—they were just part of the overall comic mayhem.

Clockwise from top left: gangsters, guns and cars in Dillinger; a Dodge Charger in Steve McQueen film Bullitt; Tippi Hedren behind the wheel of a DB2, arriving at Bodega Bay in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds; Kenneth More and Kay Kendall in a Spyker in Genevieve

The same was true of the classic gangster movies of the 1930s (Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, Scarface), many of them produced by Warner Bros. We can picture the cars used in these films in our mind’s eye—long, sleek, fast and dark, capable of taking a corner of a city street at speed, all tyres squealing. But back then, few gave much thought to their marque or model: the most important part of these cars was their running boards, big and wide enough for a mobster to stand on and unleash rounds of machine-gun fire at pursuing cops or into restaurants frequented by a rival gang. The same is true of later 1930s-set gangster films such as Dillinger (1973) and Public Enemies (2009).

Of course, millions of people were fascinated by cars, whether as vehicles for everyday use, racing or leisure. In 1932 Warner Bros., alert to the trend, released the first film of the sound era that centred on auto racing. The Crowd Roars starred James Cagney as a successful racing driver with a hotshot younger brother who fancies himself as a rival. Warners even made great play of the fact that Harry Hartz, a famous pro racer who had made his name in the Indy 500, was the real driver in the long-shot racing sequences.

But 1932 movie technology was too rudimentary to make the film feel convincing; when we see Cagney at the wheel, he’s clearly in the studio, in front of a clunky back projection of the racetrack. The Crowd Roars was aimed mainly at Cagney fans rather than car enthusiasts. In fact, it took more than 50 years before the movie world came up with a story—a series of stories, as it turned out—in which a car and a character became inextricably linked in a seemingly effortless synchronicity of mutually reflecting values, attitude and style. The car? The Aston Martin DB5. And the character? The name’s Bond. James Bond.

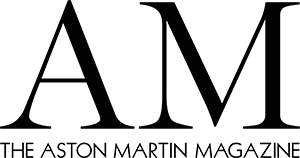

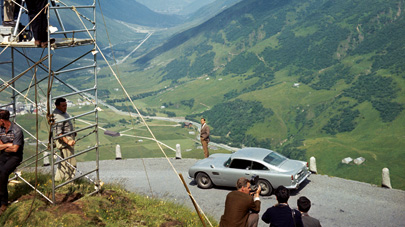

It didn’t happen immediately. The first appearance of the DB5 in a Bond film was Goldfinger (1964), the third in an already successful franchise. And it was the result of artistic license: Bond author Ian Fleming had written Goldfinger in the late 1950s, and in the book his preferred vehicle for his spy hero was the DB Mark III. But that was a racing car, and seemed an unlikely choice. The leading lights at EON, the company that produces the Bond films, cast their eyes over the DB5, which first went into production in 1963; it was a luxury tourer, which they found far more appropriate for Sean Connery. With a customised paint job that rendered it in a distinctive, classily understated Silver Birch colour, it became the classic Bond car and it appeared again in Thunderball (1965), the next in the series.

Sean Connery gets ready for a shot in Goldfinger

Why are the cars that Bond drives such a big deal? It’s not just because these films are so successful, though that doesn’t hurt. It’s mainly because Bond is a discerning man in every facet of his life. He’s fastidious about what he eats, what he smokes and what he wears. When it comes to a favourite weapon, only the Walther PPK will do. The world knows how he likes his martinis: shaken, not stirred. The women he encounters, who end up on his arm and in his bed, are always strikingly beautiful. By implication, the same principles hold good for his car. Bond doesn’t need to say a single word of dialogue in praise of his DB5—his practised ease behind the wheel in the films’ action and chase scenes say it for him.

Intriguingly, the DB5 went absent from Bond movies for three decades. Other Aston Martins were occasionally seen: the DBS in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), and the V8 Vantage Volante in The Living Daylights (1987). Other cars—Bentleys, BMWs, even a Range Rover—made appearances. But as Bond producer Michael G. Wilson observes: “We always seem to come back to Aston Martin.”

It’s especially true when the Bond franchise is at a critical juncture. The DB5 made a comeback in 1995 in GoldenEye, the first Bond movie to star Pierce Brosnan. It returned again for Casino Royale (2006), which marked Daniel Craig’s debut in the lead. Whenever these films need re-booting—in a way that signifies a new chapter while staying true to the classic values that made them hits in the first place, the DB5 is front and centre. In last year’s Skyfall, which has become the highest-grossing Bond film in history, it wasn’t just any DB5 that was used, but the original car seen in Goldfinger—the Silver Birch model with its iconic registration plate: BMT 216A. It features heavily near the film’s climax when Bond drives M (Judi Dench) to his remote ancestral home in the Scottish Highlands. “There’s something about that last part of the movie—it could have taken place in 1962,” director Sam Mendes observed. Certainly the DB5 doesn’t look out of place.

Tippi Hedren behind the wheel of a DB2 in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds

But then Aston Martins rarely do on a big screen, especially with a dashing actor at the wheel. It doesn’t need to be someone playing James Bond—Michael Caine looked the part in The Italian Job (1969), the classic caper film in which he played the suave gangster Charlie Croker. He drove a DB4 convertible, which he collected immediately on his release from Wormwood Scrubs. Once again, the car and the character suited each other—but the joke was that Caine, then in his mid-20s, couldn’t even drive it. (He finally passed his driving test at the age of 50.) Scenes in the film showing Charlie at the wheel had to be edited carefully. And still Caine looked good. Not that one even has to be male to look good in an Aston Martin. There’s a breathtakingly glamorous scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s horrific suspense thriller The Birds (1963), in which Tippi Hedren, playing a striking young socialite, who has driven from San Francisco in her Aston Martin DB2, arrives in the small, remote northern California town of Bodega Bay, where she will undergo a trial by ordeal from predatory birds.

In that moment of her arrival, looking down on the bay, she is simply a beautiful woman driving a gorgeous car. The scene has added resonance now, years later, as we have learned more of Hitchcock’s voyeuristic, even sadistic treatment of Hedren, his latest “Hitchcock blonde”, during the filming of The Birds. But there she is, looking perfect in her perfect DB2: one object of desire inside another.

Clockwise from top left:Daniel Craig makes his Bond debut in classic style with the DB5 in Casino Royale; Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis on the run from the FBI in Thelma and Louise; Christopher Lloyd and Michael J. Fox with the gull-winged DeLorean in Back to the Future III

There’s a certain frisson in watching women characters driving cars fast, especially when it constitutes bad behaviour. In Ronin (1998), British actress Natascha McElhone, not usually cast in action movies, navigates a BMW brilliantly at speed through Parisian streets in a lengthy car chase with a fiery climax. And then there’s the greatest of all female road movies, Thelma and Louise (1991), in which Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis take to the highway in a 1966 Ford Thunderbird convertible for a vacation that turns ugly. After Louise (Sarandon) shoots dead a man who was attempting to rape Thelma (Davis), the T-Bird becomes a getaway car as the two women try to stay ahead of the FBI men chasing them. It’s thrilling stuff, as well as a landmark in car movies. Significantly, driving on the open road spells freedom to Thelma and Louise, as it does in so many movies. Remember American Graffiti (1973), in which Richard Dreyfuss, playing a young would-be writer who feels trapped in a small town, comes to feel encouraged to escape by the sight of a mysterious blonde girl (Suzanne Somers) driving a white 1956 T-Bird?

Clockwise from top: Kristen Stewart in a 1949 Hudson in an adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road; Ryan Gosling’s career-defining role as a getaway driver in Drive; Michelle Rodriguez and Vin Diesel in Fast and the Furious

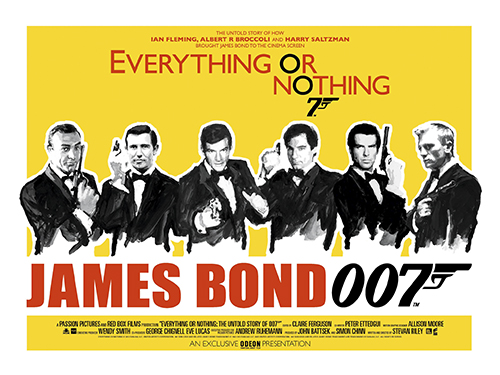

Everything or Nothing is the thrilling and inspiring story behind the Bond franchise. With unprecedented access to both the key players involved and EON Production’s extensive archive, this is the first time the inside story has been told on the big screen. Director Stevan Riley follows a story that begins with a groundbreaking spy thriller and continues with six Bonds over five decades. For more details and to order copies, go to: www.007.com/everything-or-nothing-on-dvd

Last year’s film version of Jack Kerouac’s classic 1957 Beat novel On the Road starred Sam Riley, Garrett Hedlund and Kristen Stewart as drifters criss-crossing America on the ultimate hedonistic road trip. The car that transports them? A 1949 Hudson, just as Kerouac specified. But then cars in movies can have all sorts of functions. They can be a form of time-travel: consider the ingenious use of the iconic gull-winged DeLorean in the Back to the Future films (1985-1990). They can capture the thrills of illegal street racing, as in the Fast and the Furious franchise. Vintage cars can inspire gentle affection, as two from 1904—a Darracq and a Spyker—did in Genevieve (1953). Set at the London-Brighton Veteran Car Run, it became one of the most beloved film comedies of its decade.

And sometimes the arrival of a car on the big screen can make a routine movie something else entirely. You might find yourself watching a film like Quantum of Solace, and being gripped by a spectacular three-minute car chase with Daniel Craig as Bond in his Aston Martin DBS, being pursued by baddies in a black Alfa on winding, traffic-heavy roads near Siena in Italy. It leaves you with sweaty palms. Your jaw is sagging in disbelief. You can feel your heart beating in your rib cage. And it makes you think: cars and movies—they are made for each other.

CENTENARY

Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE