Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE

CENTENARY

A SPORTING HERITAGE

Having started life in hill climbs, the Aston Martin name is synonymous with motor racing and a sporting approach and attitude, which still thrives today among its customers and partners.

Words: Brian Laban

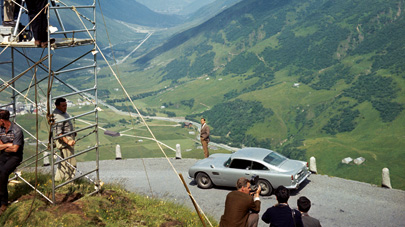

Count Louis Zborowski competes in the Midland Automobile Hillclimb at Shelsley Walsh in 1922

IN 1913, LIONEL MARTIN AND ROBERT BAMFORD founded a car repair business in Kensington; in 1914 Martin designed a sporting prototype, with a four-cylinder Coventry-Simplex engine. It might have been called a Martin, or Bamford Martin, but Lionel Martin was also a seasoned hillclimb competitor, notably with his 10hp Singer at the Aston Clinton Hillclimb, near Aylesbury.

When he eventually registered his own car, in March 1915, he called it an “Aston-Martin” (his wife Kate apparently reasoning that the “A” would put the company near the top of any alphabetic list, while the hyphen lasted on and off into the 1930s).

That car was denied its competition ambitions by World War I, but by 1919 Martin had developed another 12hp version. In June 1919, covering the London-Edinburgh 24 Hours Run, The Autocar noted: “The Aston Martin, designed and built by the well-known competition driver, Lionel Martin, attracted great attention. This car has seen much service since it was first built, but is good for any number of competitions yet.”

Lionel Martin gives the marque its maiden race victory at Brooklands

Martin’s first 1.5-litre production cars were also primarily for competition customers, and he didn’t really start selling cars to “ordinary” users until 1923, but those, too, frequently found a sporting life—excelling at Brooklands, with sprint records, a Test Hill record for H Kensington Moir, then long-distance records by the famous car “Bunny”. In 1921, Martin challenged Bugatti agent Major Lefrère to a match race, using the car with which he’d recently won the Essex Short Handicap race. But the contest (for a £50 wager) was called off after the Bugatti crashed during preparations. Competition encouraged Aston Martin to become early adopters of all-wheel brakes, and in 1923 they created a streamlined, ultra-narrow single-seater, nicknamed “The Oyster” because of its unusual opening cockpit cowl.

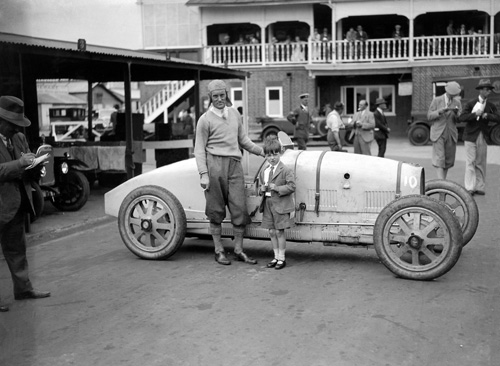

Malcolm Campbell and his son Donald, both of whom would become world land-speed record- holders

Also in 1923, Aston Martin acquired a London agent, Malcolm Campbell, who was already courting global fame. Born in 1885, the son of a London diamond merchant, Campbell raced motorcycles from 1906 and cars from 1910, his blue-painted racers famously named after Metternich’s play The Blue Bird. In World War I, he served in the army and fledgling RAF, almost being shot mistakingly as a German spy in France, and courting death while flying. By 1920, he was selling sporting and racing cars, including Peugeot, Sunbeam, Talbot and Mors, in Piccadilly, and added Aston Martin before setting the first of nine land-speed records, in 1924. Up to 1939 he would add four water-speed records; and he was flamboyant as well as wealthy, building large-scale model railways, breeding pedigree dogs, and sailing the South Seas in search of lost treasure.

His was a generation of Boys’ Own Paper-style heroes. In 1923, the very first entry for an ambitious French endurance race was a privately entered Bentley, and subsequent Bentley exploits helped the new Le Mans 24 Hour race achieve a massive British following that has defined it ever since. Between 1924 and 1930, Bentley scored five outright wins in the greatest of all endurance races and “The Bentley Boys” became national heroes.

The Bentley boys raced hard and partied harder

Prominent among them were H “Bertie” Kensington Moir, Aston Martin’s Brooklands record- breaker, and “Sammy” Davis, a noted motoring writer. “Benjy” Benjafield was a bacteriologist and founding member of the British Racing Drivers Club. Lt Cdr Glen Kidston RN was a member of a Scottish ship-building dynasty. Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin, deeply superstitious and fearsomely brave, championed the “Blower” Bentleys, despite them being reviled by founder WO Bentley, and never achieving success at Le Mans. Woolf “Babe’” Barnato’s millionaire father was half-owner of South Africa’s Kimberley Diamond Mines and Lifetime Governor of diamond traders De Beers. “Babe” would become a three-time Le Mans winner, and in 1925 temporary financial saviour for Bentley.

Aston Martin would follow Bentley to Le Mans in 1928, becoming the cars to beat in the 1500cc division. And as Barnato helped fund Bentley, Aston Martin had a patron who could rival any Bentley Boy for wealth or style. Count Louis Zborowski inherited his title in 1902, aged seven, when his father Eliot died on La Turbie hillclimb, and his vast fortune (including large areas of Manhattan and the huge Higham Park estate in Kent) when his mother, a daughter of the Astor family, died in 1911. With engineer Clive Gallop (later associated with both Bentley and Aston Martin), Zborowski built a series of monster aero-engined cars—two Chitty Bang Bangs (inspiring Ian Fleming’s later children’s stories), the “White Mercedes”, and the Higham Special, which became JG Parry Thomas’s ill-fated Babs record-breaker.

Zborowski contributed around £10,000 to Aston Martin coffers for two twin-overhead camshaft 16-valve racers, which Zborowski and Gallop raced in the 1922 GP at Strasbourg. Both retired with magneto problems, but The Motor noted: “It was very unfortunate that such Herculean little cars, which had shown a clean pair of heels to eight-cylinder vehicles, should have developed such unusual troubles.” Zborowski raced a Bugatti at Indianapolis and a Miller at Monza in 1923, joined the Mercedes team in 1924, but died at Monza that year, aged just 29, when he might well have continued his association with Aston Martin.

Zborowski in the 1924 Essex Club Kop Hillclimb

Under Aston Martin’s new proprietors, William Renwick and Augustus Cesare Bertelli, the company developed an engine designed by Bertelli. Born in Genoa, schooled in engineering in Cardiff, then in Fiat’s experimental department, “Bert” had been riding mechanic in Nazzaro’s winning Fiat in the 1908 Bologna race and won his class in the 1922 Tourist Trophy. At the 1927 Olympia Show, his 1.5-litre overhead-camshaft Aston Martin launched a generation to challenge the best in the world. LM1 and LM2, with two-seater bodies by Bert’s brother Harry, delivered Aston Martin’s 1928 Le Mans debut. Both cars retired, but one won the Rudge Whitworth Cup for its performance in the early stages, and evolved into the International from 1929 to 1932. Bertelli Aston Martins also contested the TT, Brooklands Double Twelve and Irish GP. In 1929, The Autocar remarked on “the very visible effect of sports-car racing upon the development of the ordinary super-sports, or speed model, production car”.

Yet racing was expensive, prompting further investment from HJ Aldington (of Frazer Nash) and Lance Prideaux-Brune, an enthusiastic rally driver from a Cornish family that had lived in the Prideaux Place estate in Padstow since 1535 and could trace its roots to William the Conqueror and Edward I. Prideaux-Brune’s Winter Garden Garages in Holborn held an Aston Martin agency, and Lance not only put money into the company but also worked with the Le Mans team in the early 1930s.

A female mechanic working as part of the Aston Martin team at Le Mans in 1934

Bertelli had gone back there in 1931, starting a run of 1500 class wins repeated in 1932, 1933 and 1935, when seven Ulsters entered and scored a remarkable third overall. An Ulster also won the 1500 class of the 1935 Mille Miglia, but 1934’s Le Mans travails prompted Bertelli to change the colour of the works cars for the TT from “unlucky” green to red; Aston Martin ended their pre-war Le Mans run with another 1500 win in 1937. Bertelli retired (to become a champion pig-breeder), but every Aston Martin of the period used developments of his first engine, and the International, Le Mans, Speed Model and Ulster could all claim to be race-bred.

Industrialist David Brown took over the company in 1947 and introduced the 2-litre DB1 in 1948. He also acquired Lagonda, the marque that won Le Mans outright in 1935, as well as Lagonda’s WO Bentley-designed 2.6-litre twin-cam six cylinder engine, quickly adopted for the DB2, under a fastback body based on a Le Mans version of the DB1.

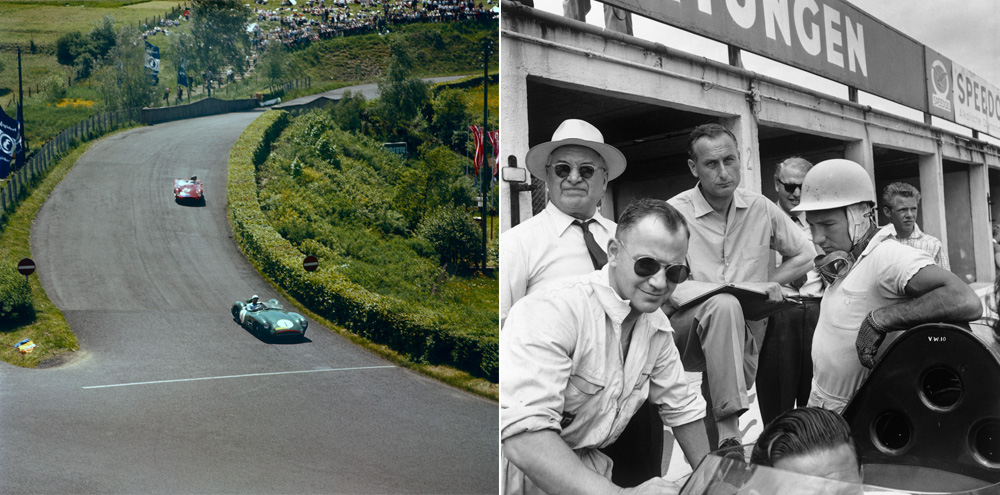

The 1950s were another Le Mans golden age, managed by John Wyer (whose planned one-year stay lasted more than 13), also bringing two Mille Miglia class wins, three Goodwood Nine-Hours, three Nürburgring 1000km, and a 1953 TT 1-2. From the start, there were tantalising glimpses of outright winning potential at Le Mans, with the DB2 and DB3S and drivers of the calibre of Peter Collins, Stirling Moss (never a Le Mans enthusiast) and Paul Frère.

Left: a rarely seen colour picture of Sir Stirling Moss on his way to victory in the DBR1 at the Nürburgring in 1958. Right: Moss and members of the support team in the pits during that same race

The decade brought five wins and seven overall podiums, against Ferrari, Jaguar and Mercedes-Benz among others, as the DBR1 became a potential winner every time out. In the 1959 Le Mans, car-dealer-turned-GP-driver Roy Salvadori paired with Texan chicken farmer Carroll Shelby, who had a heart murmur he didn’t like to mention. Brilliantly managed by Wyer, they ran a fast but disciplined pace while Moss’s speed helped break the chasing Ferraris, kept their nerve as the surviving Ferrari pulled away during Sunday, then failed, leaving Shelby and Salvadori, and Frère and Maurice Trintignant, to a superb 1-2.

“The 1950s were another Le Mans golden age for Aston Martin, managed by John Wyer (whose planned one-year stay lasted more than 13)”

Crowning this greatest year, Aston Martin beat Ferrari to the World Sports Car Championship, winning another TT and Nürburgring 1000km, then withdrew from sports-car racing, as David Brown (having seen fellow industrialist Tony Vandervell’s Vanwalls) briefly explored GP racing. His first single-seater appeared in 1956 but never raced; the DBR4 ran late in 1957 but deferred to the sports cars through 1958; 1959’s DBR4/250 again took second place to the sports-car campaign (as well as in the Silverstone F1 International Trophy, which was its best result). By 1960, the front-engined DBR5, although lighter and more powerful, had missed the boat, as every front-running GP car was now mid-engined. So after the 1961 British GP, Aston Martin’s F1 programme was quietly shelved.

Between works and customer efforts, Aston Martin never really left sport-car racing, though. In 1960, Salvadori and Jim Clark (brilliant in the wet) were third at Le Mans in the DBR1. And other 1960s ventures included the DBR1/300 prototypes, DB4GT Zagatos and 212GT prototype. But it was 1977 before the AM V8 next troubled the Le Mans score-sheet, with a 5-litre class-win on Aston Martin’s first appearance for more than 12 years.

James Hunt, Sir Stirling Moss and Roy Salvadori (seated in the DBR1) at the launch of the Nimrod 2 race team, backed by Victor Gauntlett, in 1981

From 1980, the then Aston Martin Chairman Victor Gauntlett backed the Nimrod Group C programme (which survived to 1984), while Michael Cane Racing ran the Len Bailey-designed 5.3 V8-powered Group C EMKA from 1983. And there was a “works” return in 1989 (under Ford) when two ambitious, carbon-tub 6-litre V8 AMR-1 Group C cars carried black stripes in honour of John Wyer, who had died a few weeks before the race, with one surviving to finish eleventh overall.

In 2005, Aston Martin Racing returned to its GT roots, challenging Corvette and Ferrari with the GT1 DBR9, and winning first time out, in Sebring. From pole, they might have won Le Mans, too, but a dominant performance was ultimately ruined by punctures and accident damage. 2006 brought the Le Mans Series title (through Larbre Competition), and FIA GT1 Manufacturers’ Cup; and in 2007, after an epic GT1 confrontation, the pale green DBR9 made AMR a Le Mans class winner again. In 2008, wearing iconic pale blue and orange Gulf livery, they won again; three of the four DBR9s finished, the winner made no unplanned pit stop, and spent less time in the pits than any other car in the GT1 field.

“A string of podium finishes set up AMR’s most ambitious GT programme for the 2013 WEC with four Vantage GTEs”

For drivers such as Darren Turner, Tomás Enge, Pedro Lamy, Stefan Mücke, Harold Primat, Johnny Herbert, David Brabham and Heinz-Harald Frentzen, Aston Martin’s works and partner teams had become almost as much of a family as the Bentley Boys had been in the 1920s.

Charouz Racing’s 2008 Aston Martin-powered LMP1 coupe tested the prototype water, and snatched second in the “petrol” ranks behind the now unbeatable diesels. Then, AMR’s 2009 LMP1 return brought two Gulf-liveried works cars alongside returning Charouz, eyeing another outright win, 50 years on. But after two more years leading the “petrol” challenge against big-budget diesel teams, and a final tilt with the all-new AMR-One in 2011, 2012’s Vantage-based attack on the World Endurance Championship took Aston Martin back to its production-based GT roots, to compete again for real rather than qualified wins.

A Vantage GT3 continues the marque’s racing tradition in the 2013 24-hour race at the Nürburgring

Bruno Senna, nephew of the late, great Ayrton, joined Aston Martin Racing for the 2013 World Endurance Championship

A string of podium finishes have set up AMR’s most ambitious GT programme for 2013, with four Vantage GTEs for the WEC (and drivers including Bruno Senna, nephew of the great Ayrton), plus five cars for Le Mans. Once again, Aston Martins will contest GT3 and GT4 series—recent GT4 drivers include Aston Martin Chairman David Richards and Red Bull F1 boss Christian Horner. And Aston Martin was again at the Nürburgring 24 Hours, where the Rapide, Zagato and Vantage have proved their pedigree in recent years, with CEO Dr Ulrich Bez among the drivers.

This year’s Nürburgring race saw the debut of the Hybrid Hydrogen Rapide S and the first ever “zero-emission” lap in a major race. “As we look back on a century of excitement, innovation and style, it’s also the perfect time to look to the future with this astonishing race car,” says Dr Bez. David Richards agrees: “There’s a real sense of anticipation in the Aston Martin Racing team this year and a belief that it is once again our time to return to the top step of the podium at Le Mans. It would be a fitting way for Aston Martin to cap its centenary year.” The philosophy is still in safe hands.

CENTENARY

Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

- 100 YEARS OF ASTON MARTIN

- ARCHIVE